3D-Aware Scene Manipulation via Inverse Graphics

Abstract

As humans, we are renown at perceiving the world around us and simultaneously make deductions out of it. But, what is interesting and also magnificient is that as we do perceive the world around, we are also able to simulate and imagine in what ways changes can appear unto our perceptions for future scenarios. For instance, we can, without showing much effort, detect and recognize cars on a road, and infer their attributes. At the same time, we have also a special power by which we could imagine how cars may move on the road, or they will ever rotate right or left, or we can even wonder about what might be a more plausible color the car may have other than the driver’s choice.

Motivation arises from this very specific human ability. Can we enable a neural network architecture gain such ability?

Introduction

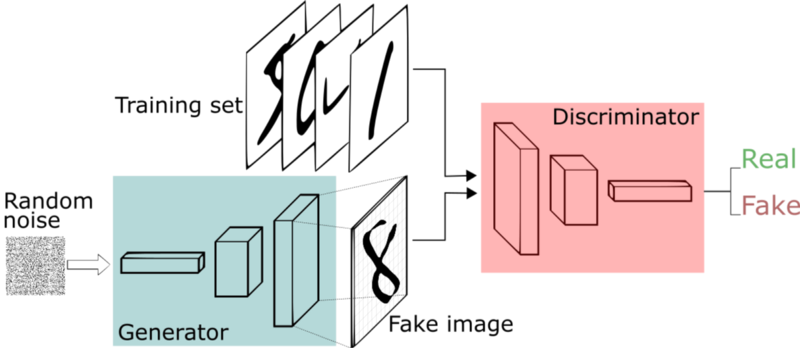

To grant that ability to the machines, we should let them understand given scenes and encode given scenes into latent space representations. From those intermediate representations, they should also be able to generate plausible images back. And actually, deep generative models and specifically Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [Goodfellow et al., 2014] excels at this duty with their terrific and simplistic encoder-decoder architecture. In a GAN setup, two differentiable functions, represented by neural networks, are locked in a game. The two players (the generator and the discriminator) have different roles in this framework. The generator tries to produce data that come from some probability distribution (namely the latent-space representation) and the discriminator acts like a judge. It gets to decide if the input comes from the generator or from the true training set. However, deep generative models have their flaws in which latent-space representations are often limited to a single object, not easy to interpret, and missing the 3D structure behind 2D projection. As aresult, deep generative models are not perfectly fit for scene manipulation tasks such as moving objects around. Additionally, as it is a scene manipulation task at hand, it is needed to have human-interpretable and intuitive representations so that any human user or a graphics engine is enabled to use.

In this paper, motivated by the aforementioned human abilities, authors propose an expressive, disentangled and interpretable scene representation method for machines. The proposed architecture elaborates an encoder-decoder structure for the main purpose and divides different tasks to three separate branches: one for semantics, one for geometry and one for texture. This separative and human-interpretable approach also overcomes the mentioned flaws of the deep generative models. By adapting this architecture, it is further possible to easily manipulate given images.

Related Work

As said before, thw whole proposed method is consisted of three different pipelines: first an interpretable image representation is obtained for the given image, second another pipeline takes those interpretable representations of the given image and tries to synthesize an realistic image back, third but not least enables its user to edit images in anyway imagined since disentangled and human-interpretable representations is at hand. Therefore, inspiration for the proposed method comes from three different sets of state-of-art work:

- Interpretable image representation

- Deep generative models

- Deep image manipulation

Authors cancel out the flaws of prior works by combining the best features of all mentioned methods below.

Interpretable Image Representation

The main idea behind inverse graphics and obtaining image representations is to reverse-engineer an given image such that end-product can be used to understand the physical world that produced the image or edit the image in various way since the world behind is viable to such manipulations after getting to know it.

This work is inspired by prior work on obtaining interpretable image representations by [Kulkarni et al., 2015] and [Chen et al., 2016]. [Kulkarni et al., 2015] proposes and deep neural network which is composed of several convolution and de-convolution layers. It is called Deep Convolution Inverse Graphics Network (DC-IGN) and the model learns interpretable and disentangled representations for pose transformations and lighting conditions. Given a single image, the proposed model can produce different images of the same object with different poses and lighting variations.

Another line of inspiration comes from the InfoGAN [Chen et al., 2016]. InfoGAN proposes to feed traditional, vanilla GAN [Goodfellow et al., 2014] with two disentangled vectors, namely ‘noise vector’ and ‘latent code’, rather than just simply submitting an single noise vector. Thus, as having two different ‘turn knobs’ for the images (one for the regular noise input for manipulations, and one for the class encoding so that while preserving the latent code same, one can make manipulations on the noise input in various way to edit end-image), it is easy to obtain disentangled and easy-to-manipulate representations.

But the problem with those two powerful implementations is that they are limited to single objects, whereas overall aim of the proposed method is to have an scene understanding model which captures the whole complexity in images with multiple objects. Therefore, this paper most resembles the work by [Wu et al., 2017] in which it is proposed to ‘de-render’ the given image with an encoder-decoder framework. While encoder part uses a classical neural network structure, the decoder part is simply a ‘graphics engine’ for which encoder produces human-readable and interpretable representations. Although graphics engines in their nature require structured and interpretable representations, it is not possible to back-propagate gradients end-to-end because of their discrete and non-differentiable characteristics. Rather, they use an black-box optimization via REINFORCE algorithm [reinforce et al.,]. Compared to this work, the proposed method in this paper uses differentiable models for both encoder and decoder parts.

Deep Generative Models

Deep generative model is a powerful way to learning rich, internal representations in a unsupervised manner and using those representations to synthesize realistic images back. But, those rich and internal latent representations are hard to interpret for humans and more of than not ignore 3D characteristics of our 3D world. Many work have investigated ways of 3D reconstruction from a single color image[Choy et al., 2016, Kar et al., 2015, Tatarchenko et al., 2016, Tulsiani et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2017b], depth map or silhoutte[Soltani et al., 2017]. This works is built upon those proposals and extended them. It does not only reconstructs the image from internal representations via 2D differentiable renderer, but also does it provide an 3D-aware scene manipulation option.

Deep Image Manipulation

Learning-based methods have enabled their users in various tasks, such as image-to-image translation [Isola et al., 2017, Zhu et al., 2017a, Liu et al., 2017], style transfer [Gatys et al., 2016], automatic colorization [Zhang et al., 2016], inpainting [Pathak et al., 2016], attribute editing [Yan et al., 2016a], interactive editing [Zhu et al., 2016], and denoising [Gharbi et al., 2016]. But the proposed method differs from those methods. While prior work focuses on 2D setting, proposed architecture enables 3D-aware image manipulation. In addition to that, often those methods require a structured representation, proposed method can learn internal representations by itself.

Also, authors take inspirations from semi-automatic, human-aware, 3D image editing systems. [Chen et al., 2013, Karsch et al., 2011, Kholgade et al., 2014].Whereas the proposed method is fully automatic while obtaining object geometry and scene layout, those early works require human annotations to infer to pre-edit images before obtaining any features from the given images.

Method

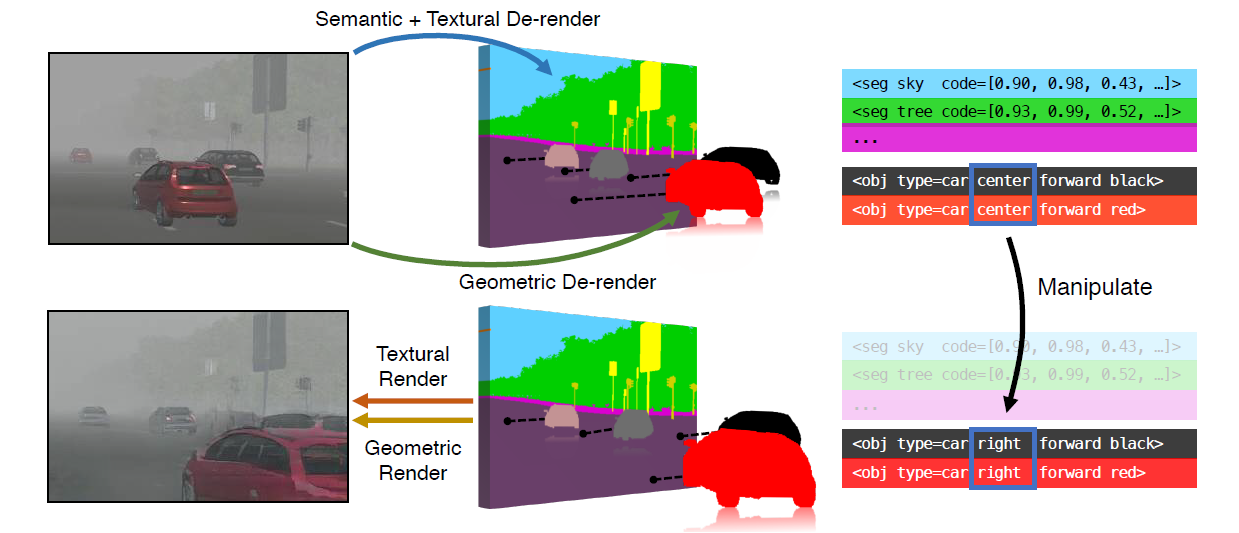

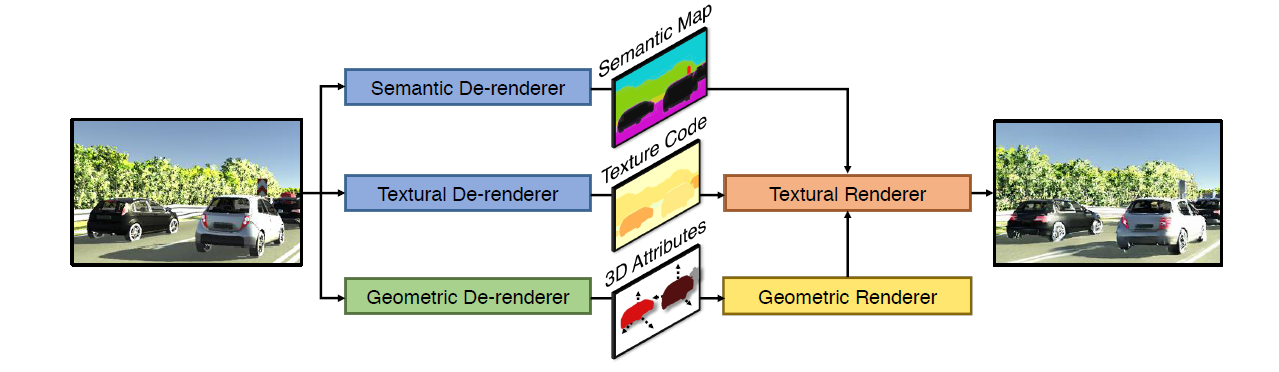

In the paper, authors propose a 3D scene de-rendering network (3D-SDN) in an encoder-decoder framework. As it is said in the introduction chapter, network first de-renders (encodes) an image into disentangled representations for three information sets: semantic, geometric and textural. Then, using those representations, it tries to render (reconstruct, decode) the image into a plausible and similar copy.

Branches and Pipeline

Mentioned pipeline branches are decoupled into two parts: de-renderer and renderer. While semantic branch doesn’t have any rendering part, other two parts of the pipeline (namely, geometric and textural) first de-render the image into various representations and for last textural branch combines different outputs from different branches (including its outputs) and tries to generate a plausible image back. Let us see what each parts do individually.

Semantic Branch

Semantic branch does not employ any rendering process, at all. One and only duty of the semantic branch is learning to produce semantic segmentation of the given image to infer what parts of the image are foreground objects (cars and vans) and what parts are background (trees, sky, road). For the purpose, it adopts Dilated Residual Network (DRN) [Yu et al., 2017].

Geometric Branch

Before anything fed into the inference module of the geometric branch, object instances are segmented by using Mask R-CNN [He et al., 2017]. Mask R-CNN generates an image patch and bounding box for each detected object in given image. And afterwards, geometric branch tries to infer 3D mesh model and attributes of each object segmented, from the masked image patch and bounding box. So how does it do that?

An object present in the given image is described via its 3D mesh model , scale , rotation quaternion and translation from the camera center . For the simplicity, it is assumed that objects lie on the ground and therefore have only one rotational degree of freedom for the most of the real-world problems. Therefore, they do not employ the full quaternion and convert it to a one-value vector, . After defining the attributes of geometric branch, let us describe how they formulate the training objective for the network.

3D Attribute Prediction Loss

The de-renderer part directly predicts the values of and . But, for the translation inference, it is not straightforward compared to others. Instead, they separate the translation vector into two parts as one being the object’s distance to camera plane, and the other one is the 2D image coordinates of the object’s center in 3D world, . Combining those two and given intrinsic matrix of the camera, one can implement the of the mentioned object.

To predict , first they parametrize in the log-space [Eigen et al., 2014] and reparametrize it to a normalized distance where is the width and height of the bounding box, respectively. Additionally, to infer , following the prior work in Faster R-CNN [Ren et al., 2015], they predict the offset distance from the estimated bounding box center , and thus the estimated offset becomes .

Combining all those aforementioned attributes in a loss function yields one of the training objectives of geometric de-renderer part as,

where denotes the respective predicted attribute.

Reprojection Consistency Loss

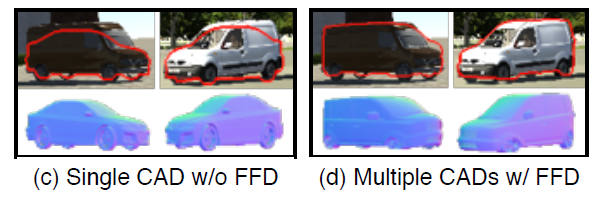

Another training objective of the geometric de-renderer part is ensuring the 2D rendering of the predicted 3D mesh model matches its silhoutte so that 3D mesh model with the Free-Form Deformation (FFD) [Sederberg and Party, 1986] parameters best fit the detected object’s 2D silhoutte. This is the reprojection loss. It should also be noted that since they have no ground truth 3D shapes of the objects in images, reprojection loss is the only training signal for mesh selection and silhoutte calibration (namely finding the deformation parameters).

To render the 2D silhoutte of 3D mesh model, they use a differential renderer [Kato et al., 2018], according to the FFD parameters and predicted 3D attributes of the given image . By convention, the 2D silhoutte of the given 3D mesh model is a function of and : .

So, another training objective comes into the action:

All above, we defined how they achieve a training objective for consistency when they have tried to find the suitable mesh model and deformation parameters. This procedure can directly infer the deformation parameters, but mesh model selection is non-differentiable and just doing backpropagation will not take it anywhere, at all. Therefore, they reformulate the whole problem as reinforcement learning problem. They adopt a multi-sample REINFORCE algorithm [Williams, 1992] to choose a suitable mesh from a set of eight candidate meshes using the negative as the reward.

After de-rendering process, geometric de-renderer combines all information gathered from different process lines and outputs an instance map, an object map and a pose map for each given image.

Textural Branch

Now we have got the 3D geometric attributes of the objects and also the semantic segmentation of the given scene, we can infer textural features of each detected object.

First of all, textural branch combines the semantic map from the semantic semantic branch and the instance map from the geometric branch to generate an instance-wise semantic label map . Resultant label map encodes which pixels in the image are the objects pixels and whether instance class of the each object pixel belongs to a foreground object or a background object. And also, during combination, any conflict is resolved in favor of the instance map [Kirillov et al., 2018]. Using an extended version of the models used in multimodal image-to-image translation [Zhu et al., 2017b, Wang et al., 2018], a textural de-renderer encodes the texture information into a low-dimensional embedding and later a textural renderer tries to reconstruct the original image from that representation. Let us break into pieces how the whole branch de-renders and renders given image:

Given an image and its instance-wise label map , the objective is to obtain a low-dimensional embedding such that from , it is possible the reconstruct a plausible copy of the original image. The whole idea is formulated as a conditional adversarial learning framework with three networks :

- Textural de-renderer

- Textural renderer

- Discriminator

where is the reconstructed image.

Photorealism Loss

To increase the photorealism of the reconstructed images, authors employ the standard GAN loss as

Pixel-wise Reconstruction Loss

Also, to cancel out the pixel-wise differences between the original image and the reconstructed image, they use pixel-wise reconstruction loss.

Stabilizing GAN Training

GAN models can suffer severely from the non-convergence problem. The generator tries to find the best image to fool the discriminator, while discriminator tries to counterattack this proposal by labeling it as not-a-plausible reconstruction. The “best” image keeps changing while both networks are counteracting each other. However, this might turn out to be a never-ending cat-and-mouse game and model unfortunately never converges to a steady state. To overcome this and stabilize the training, authors follow the prior work in [Wang et al., 2018] and use both discriminator matching loss [Wang et al., 2018](https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.11585), [Larsen et al., 2018] and perceptual loss [Dosovitsky and Brox, 2016, Johnson et al., 2016] and both of which goal to minimize the statistical difference between the feature vectors of real image and the reconstructed image. For the perceptual loss, feature vectors are generated from the intermediate layers of the VGG network [Simonyan and Zesserman, 2015] and for the discriminator feature matching loss, as the name suggests, they are generated using the layers of discriminator network. And the overall objective becomes as

where denotes the -th layer of a pre-trained VGG network with elements. Likewise, denotes the -th layer of the discriminator network with elements.

These all objectives above, are combined into a minimax game between and :

where and are the relative importance of each objective respectively.

Implementation Details and Configurations

In this section, authors detail the implementation and trainig configuration for each branch.

Semantic Branch

Semantic branch adopts Dilated Residual Networks [Yu et al., 2017] for semantic segmentation. Network is trained for 25 epochs.

Geometric Branch

They use Mask-RCNN [He et al., 2018] for object proposal. For object meshes, they choose eight different CAD models from ShapeNet [Chang et al., 2015] as candidates. They set . They first train the network alone with using Adam optimizer [Kingma et al., 2015] by setting learning rate to for epochs and then fine-tune it with and REINFORCE with a learning rate of for another 64 epochs.

Textural Branch

They use same architecture as in Wang et al., 2018. They use two different discriminators of different scales and one generator. They set and and train the textural branch for epoch on Virtual KITTI and epoch on Cityscapes.

Results and Comparisons

Results in the paper are reported two-fold:

- Image editing capabilities of proposed method

- Analysis of design choices and accuracy of representations

The proposed method has been tested and validated upon two different datasets: Virtual KITTI [Gaidon et al., 2016] and Cityscapes [Cordts et al., 2016]. Both quantitative and qualitative experiments are demonstrated over those two datasets. Additionally, authors create an image editing benchmark on Virtual KITTI to elaborate the effectiveness of the proposed method and also to compare editing power against the 2D baseline models.

Datasets

Virtual KITTI

The dataset is consisted of five different virtual worlds rendered under ten different conditions, leading to sum of 21,260 images with instance and semantic segmentations. Each object has its own 3D ground truth attributes encoded.

Cityscapes

The dataset contains 5,000 images with fine annotations and 20,000 with coarse annotations obtained in several conditions (seasons, daylight conditions, weather, etc.) in 30 cities with 30 classes of complexity. With fine annotations, they mean deep pixel-wise annotations for each object’s semantic class. But the problem with this dataset is that it lacks 3D annotations for objects. Therefore, for each given Cityscapes images they first predict 3D attibutes with the geometric branch pre-trained on Virtual KITTI dataset, then try to infer 3D and deformation parameters.

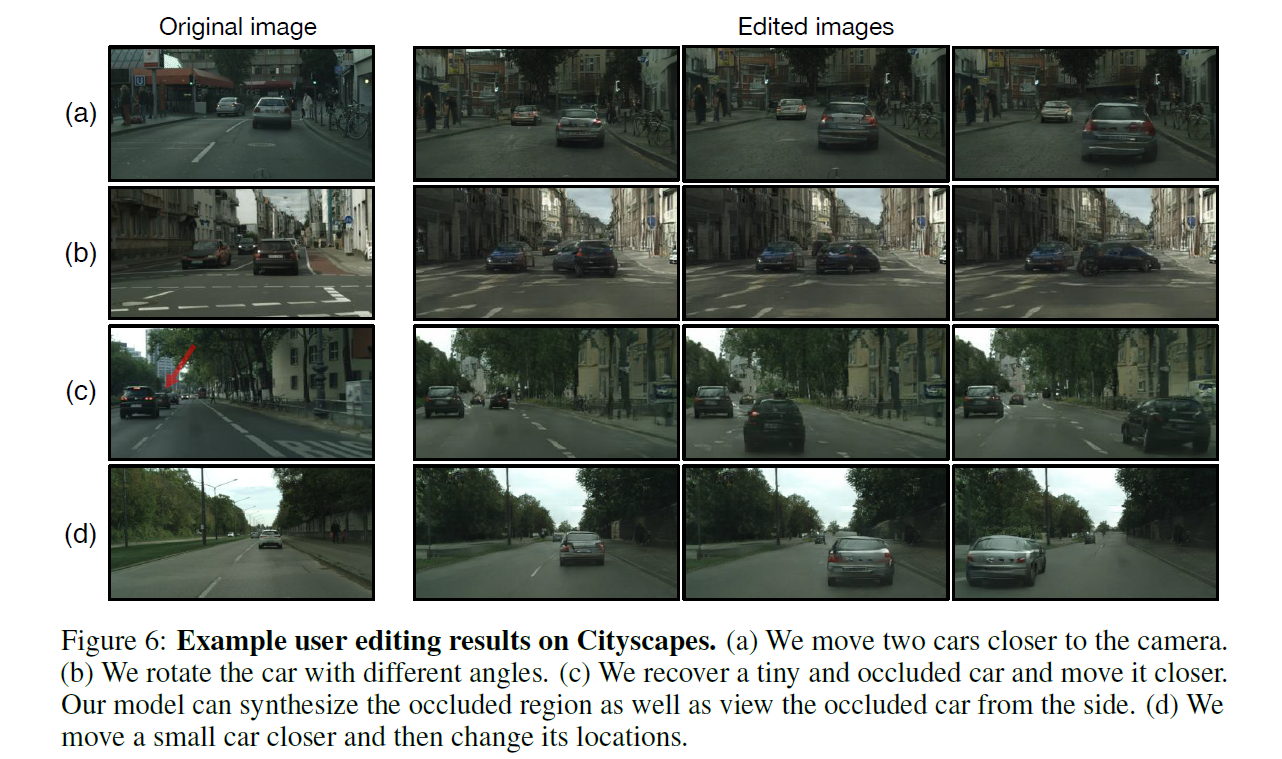

Image Editing Capabilities

The disentanglement of attributes of an object provides an expressive 3D manipulation capability. Its 3D attributes can be changed. For example, it might scaled up and down or we can rotate it however we would like to, while keeping visual appearance at still. Likewise, we can change the appearance of the object or even the background in any way imaginable.

The proposed method is compared two baselines:

- 2D: Given the source and target positions, only apply 2D translation and scaling, without rotation the object at all.

- 2D+: Given the source and target positions, apply 2D translation and scaling, and rotate the 2D silhoutte of the object (instead of 3D shape) along the axis.

To allow to evaluate image editing capabilities, they have built the Virtual KITTI Image Editing Benchmark wherein it is consisted of 92 pairs of images, with the one being the original image and the other being the edited one in each pair.

For the comparison metric, they employ Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [Zhang et al., 2018], instead of adopting the L1 or L2 distance, since, while two images may differ slightly in perception, their L1/L2 distance may have a large value. They compare proposed model and the baselines and apply LPIPS in three different configurations:

- The full image: Evaluate the perceptual similarity on the whole image (whole)

- All edited regions: Evaluate the perceptual similarity on all the edited regions (all)

- Largest edited region: Evaluate the perceptual similarity only on the largest edited region (largest)

Addition to the quantitative evaluation, they also conduct an human study in which participants report their preferences on 3D-SDN over two other baselines according to which edited result looks closer to the target. They ask 120 human subjects on Amazon Mechanical Turk and ask them whether which image is more realistic than the other in two settings: 3D-SDN vs. 2D and 3D-SDN vs 2D+.

In LPIPS metric, scores ranges from 0 to 1, 0 meaning that two images are the same. Therefore, lower scores are better. As you can see from the perception similarity scores, the proposed architecture overwhelms both baselines in every experiment setting. Likewise, in human study, users often prefer 3D-SDN over other two baselines.

Analysis of Design Choices and Accuracy of Representations

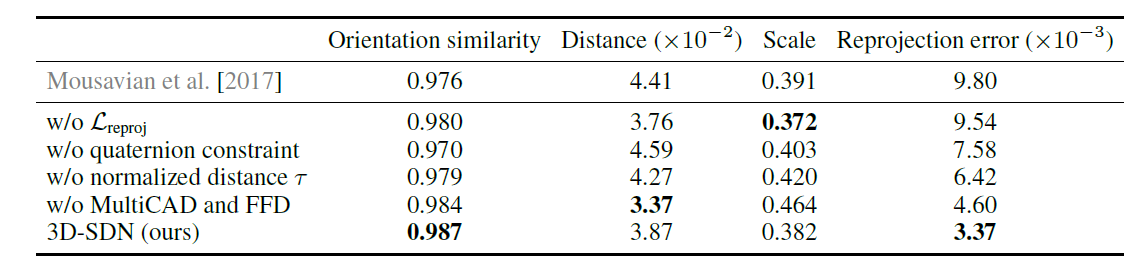

To understand contributions of each component proposed, they experiment on four diffent settings in which a different component excluded from the full proposed model ,,and compare them to the original, full model. The experiment configurations are:

- w/o : Use only

- w/o quaternion constraint: Use full quaternion vector, instead of limiting to

- w/o normalized distance : Predict the original distance in log-space rather than the normalized distance

- w/o MultiCAD and FFD: Use single CAD model without free-form deformation

They also add a 3D box estimation model [Mousavian et al., 2017], which first infers the object’s 2D bounding box and searches for its 3D bounding box, to the comparison list.

In the above figure, different quantities are evaluated with different metrics:

- For rotation, orientation similarity , where is the geodesic distance between the predicted and the ground truth

- For distance, absolute log-error

- For scale, Euclidean distance

- For reprojection error, compute per-pixel reprojection error between 2D silhouttes and ground truth segmentations

As you can see from the above figure, the smallest reprojection error and the highest orientation similarity have been met by the full model. It ultimately shows that all proposed components contribute to the final performance of full 3D-SDN model.

Conclusion and Discussion

In this work, authors propose a novel encoder-decoder architecture that disentangles semantic, geometric and textural attributes of the detected objects into expressive and rich representations. With these representations, users are enabled to easily manipulate the given images in various ways. This proposed method also overcomes the single-object limitations in its prior work and cancels out the occlusion problem. Although the main focus here is 3D-aware scene manipulation, learned distentangled and expressive representations can also be used in various tasks such as image captioning.

To my discussion, even though the proposed method eliminates couple of limitations in its prior state-of-art works, it is still limited to just one specific set of objects: vehicles. Without introducing new meshes, it is not applicable to more complex and diverse sceneries, such as indoor images. For any regular indoor image, we face lots of different types of objects. And as the number of object classes and the number of mesh types in each class increases, unfortunately overall complexity increases dramatically. Also, the model might not have the capability to handle much deformable shapes like human bodies without introducing more deformation parameters.

For the slides presented in the lecture, please follow the link.